09/11/2019 | Maria Adelaide Marchesoni

Collecting books

Double interview with the brothers Gianni and Giuseppe Garrera, art and book collectors

Why do you think one becomes a collector?

GIANNI: In the beginning because of an excess of philology, in a sense. It was like the desire to read a book in its first edition, as it appeared for the first time in the world. If it was possible I would want it in the first typescript copy, and even more in the handwritten copy, this lead to an obsession with seeing the original and the distrust if any form of reproduction, and makes one yearn to possess the original of a seen, studied and admired drawing or painting ,, but only reproduced in a volume. To put it in a half biblical and half platonic expression: one does not follow the image and the likeness, but the identity, therefore one wants the original and not the copy or the copy of the copy.

GIUSEPPE: I would say also, it instinctively arises from a desire forsplendor There is also, in the Italian identity, an obedience and irrepressible inclination and interest in principalities, kingdoms, lordships, houses and papacy, to the princely aspect of our history. I speak sincerely of a desire to be princely (regal, noble) and to have a realm that justifies the present.

And in your case? Why do you collect ?

GIANNI: The idea of accumulating at home, in our own earthly world, the hyperuranium world of original ideas, not having the shadows of books or paintings, but the lights of hyperuranium, to be honest .

GIUSEPPE: The personal reasons for our collection are also linked to a social and economic story involving many fantastic childish desires that were not fulfilled, up to make visible and admirable object of collection the years and the readings and passions, declining our history of ideas in idols and exercises for a collection that testifies to nobility

What do you collect?

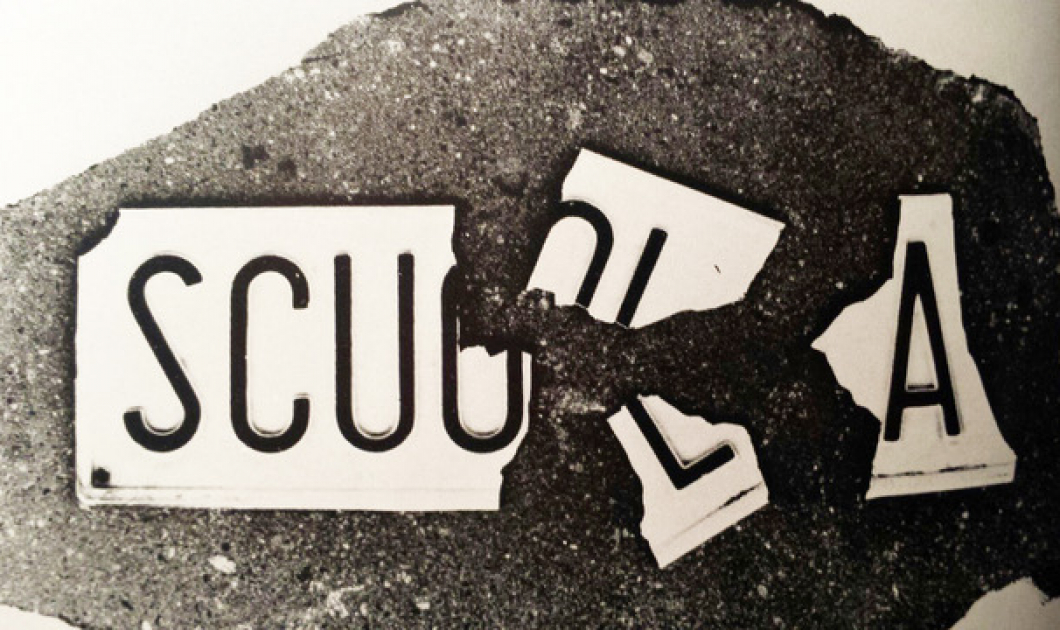

GIANNI: We collect modern and contemporary art, because we believe that it is necessary to be contemporary and enter into a relationship with the present face to face. And since it is necessary to be absolutely contemporary, then we must in the risk our skin economically. If we study a contemporary artist (practioner?) at a certain point we want to have not only one of his works, but, if possible, all of his works. For example, at the recent exhibition, the first retrospective after her death, dedicated to Mirella Bentivoglio, contains all works (about fifty pieces, which is still only a part of what we have collected of her) from our collection. This is characteristic of our ideal (impossible) collection: to collect the entire life of an artist or at least the essential works of his essential story , in all its stages, including sketches, projects, drafts, publications, letters, and therefore also the archive.

GIUSEPPE: Obviously, above all, we collect conceptual art, guerrilla art, research art, protest art, art that is not subservient to the market and the pleasures of the living room. All Italian art between the 60s and 70s. as much as possible of intellect, full of relics and fetishes and symbols of ideas and fighting, and at the center we reserve a place of privilege for female research and a hypothesis of the matriarchal regency of the world.

What aspect of collecting do you prefer: searching, finding or owning?

GIANNI: Actually, all three aspects, but in first place is the impulse for research, which is like a treasure hunt. For contemporary art the world, the earth, the soil, the homes, the galleries, are still treasure islands that hold hidden treasures. The attitude is exactly like that of an adventure is to Robert Louis Stevenson, who also followed the fantastic , from the children's pirate stories. Finding and owning are just the following of an initial fantasy.

GIUSEPPE: Yes, the best thing is to search, it belongs to a particular practice of insomnia: backs of galleries, bookstore finds, texts, traces of friendship, suggestions and casual encounters, chance, and the idea that there is still very much hidden, lost, neglected, not studied: one could say that almost all of the 20th century is still to be discovered and that looking for it is really a treasure hunt and the deciphering of maps and topographies still unknown (for example, there is an avant-garde history of the "Italian province" still to be done and archived, made up of clandestine groups, extreme experiences, intransigence, not compromising with official powers and administrations of culture). And in any case, once a thing is found it becomes a fulfilled desire and, above all, an admonition to look for more worthy companions in the growing collection. The hunt is often, a betrayal, an inspection or verification in the gardens of possession where oneis not allowed to rest and that at every turn indicates new ways of escape.

How did the collection of intellectual works come about?

GIANNI: From study, from research, never from a business model .

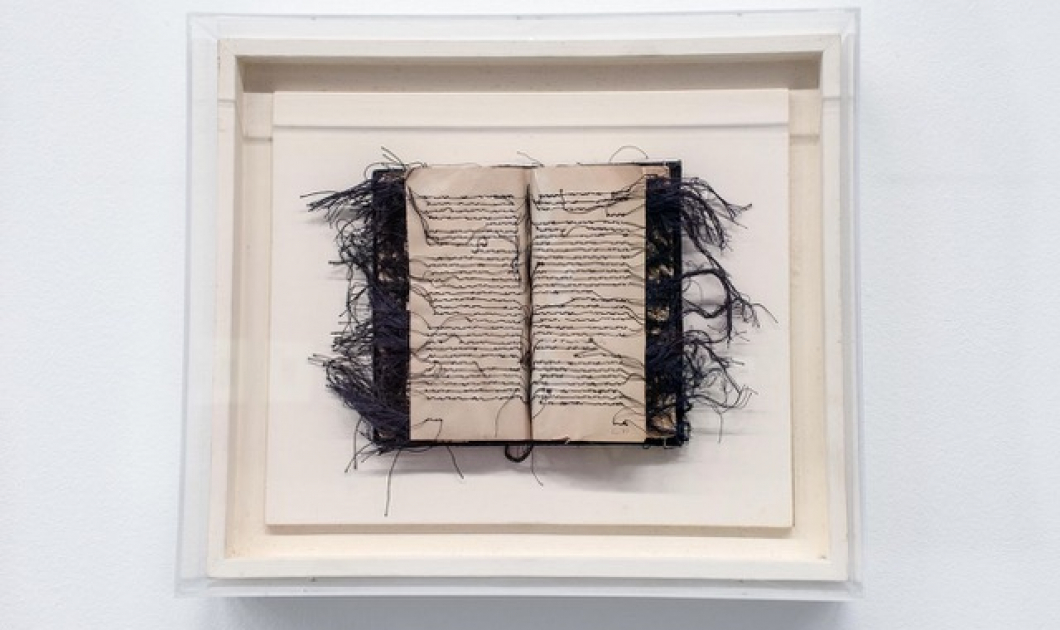

GIUSEPPE: From idolatry, from idolatrous practices: possessing the first guise and appearance of a beloved book, also in the conviction that the editorial history, the adventure of the cover, of the paper, of the lapels, of the binding, are part of the adventure and of the history of that text, its incarnation. For example, the Garzanti edition of poems by Sandro Penna with the bookmark written by Pier Paolo Pasolini, or the first Einaudi edition of Il Giovane Holden (Italian edition of Catcher in the Rye) with, the photo-portrait in the back cover of Salinger (which never appeared again ), or all the editions and re-editions of the works of Elsa Morante, each time modified and varied, by the the author, with the biographical note that forms a legend to lose all trace of herself. The wonders and the typographic adventures are endless, and I'm not just referring to dedications and interventions by hand.I just bought an edition of Impromptu by Amelia Rosselli with corrections and autographed variants by the author) or unique pieces by artists (for example I own some books by Munari made exclusively in a single copy to play with with your grandchild). Of course, the ultimatedeal is that of the treasure and prestige of having restored time and emotion.

What was your first purchase for the pleasure of possession?

GIANNI: A Ruin of Piranesi.

GIUSEPPE: A Caprice of Goya.

The “unattainable” book that became part of your collection? How, when?

GIANNI: The music score of Verdi's Nabucco played by Kounellis' pianist in 1970 at "Vitalità del negativo", at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome. In the exhibition a musician played a fragment from Nabucco on the piano and read the music from an open music score on the music stand. Kounellis indicated the exact lines to play and inserted a kind of symbol of refrain so that the piece was played each time from the beginning perpetually. That score is in our possession.

GIUSEPPE: Gino De Dominicis' 1970 catalogue published by Attico, his only catalogue (but in reality a book-work with projects, declarations, assumptions, original ideas), that De Dominicis spent the following years destroying, tracing all the copies in circulation. At the moment, there is only one other copy, apart from ours.

What is not in the collection because it is unobtainable, with the most curious story to tell?

GIANNI: An unattainable book is obviously the book that swallows the apostle John of the Apocalypse. He is given a book to eat and he swallows it. I remember talking to Mirella Bentivoglio about it, about the Alpha Book - the Book Bread that she made in 1978 with Maria Lai and that, like a Eucharist, was to be a book to eat. Actually , instead of becoming a book of communion and sharing, this became for them the book of discord, because, as Mirella told me, in the following expositions Lai entirely appropriated it and attributed it only to herself.

GIUSEPPE: A book by Pier Paolo Pasolini, the 1970 Garzanti pocket anthology. O. It is not important at the bibliophile level, except for an autograph dedication on the front page from Pasolini to Dario Bellezza, enigmatic and secret, beautiful and a testament , it escaped from under my nose by a whisker, I was not able to buy it because somebody had been there before me, and took it away like a trophy and disappeared. I regretted it and for months, blamed myself for stopping first in another bookshop with nothing special, and knowing it was an irreparable loss: until I received it, as a gift , from a dear friend, Andrea Galli, a great bookseller from Rimini, who had got it in a hurry with the very thought of surprising me with it. Strange, it had been taken away from me because of of his friendship and delicacy, causing pain you wouldn't expect from a friend! Obviously, I have never disclosed the dedication and not shown it to anyone: its secret is the seal of this dream. But in truth there are many losses and mistakes , but the most serious, in collecting, are often rewarded by admiration for collecting. For example, I always think about a splendid book by Richard Tuttle, from the Galleria di Ugo Ferranti, with each piece of paper bearing, by hand, a brushstroke like a wing coup, which I hesitated to buy , and I payed for the delay, the prudence, the delay , with its loss. Christoph Schifferli bought it immediately, without thinking about it, and I am happy (if you can say happy in these cases) because it is a supreme example for me, in my view, as a collector of artist's books of the Swiss school is unbeatable, like the German one of Max Renkel. . To be clear, the latter a sort of hunting dog with an amazing flair and who stole several treasures from me: in the past year he intercepted a book by Gerhard Richter (I cannot mention title and references here ) I don't to lose sleep over this . He owns some editorial pieces by Lothar Baumgarten, and in his collection, the drawers, are a kind of Eldorado. Sometimes I visit him only for the consolation of watching and calculating the lighting of his collection.

What is the one piece that fills you with pride?

GIANNI: A sort of instruction manual by Giulio Paolini from the '70s for a gallerist, with a list of materials and pieces to be bought, with the measurements and the map of the arrangement of each part of an installation that the gallerist had to follow remotely (Paolini writes from Turin and the gallerist is in Rome).

GIUSEPPE: A personal diary by Mario Schifano with notes, sentences, drawings, ideas, projects, memories, scribbles, addresses, appointments, telephone numbers, words, slogans: the recording of a year live and incandescent day by day. I must say that as a book and as an object it has something incredible: on every page there is a surprise and an intimacy.

Where do you go to look for them?

GIUSEPPE: Many of our searches are at junk dealers and cellars , in areas of unloading and disposal, in warehouses, in the vast and clumsy management of heirs and of deaths, bequests, , the results of the haste and inexperience or neglect of relatives: it is ideal when you can access houses before departure or inventory, then we are like like jackals or crows.

Is it possible to see your book collection?

GIUSEPPE: Not really , because it is not easy to show books, if not a selection that is valuable for its i e covers, nor do we want them to be leafed through or picked up. This might sound strange , but the collector himself is the most awkward and often the emotion is attested to by the damage he causes: the collector, the owner, is sometimes the least careful with a book. And then for those who collect books there is the extraordinary magicof the scent of sheets and glues, of the smell of the volume (a great reader can recognize it because one of the first things he does with a book is to bring it to his nose and smell it). It remains an inevitably secret collection, intimate and doomed to remain sealed.

Gianni Garrera is a musical philologist and theatre translator, editor of Kierkegaard's aesthetic works for 'Classici del Pensiero ' BUR and the new edition of Kierkegaard's Diaries for Morcelliana; and the soon to be released, by Morcelliana: Søren Kierkegaard, Rivelazione divina e genialità. He teaches "Theatre Aesthetics" at the School of Theatre of the National Mercadante Theatre in Naples.

Giuseppe Garrera is a musicologist, art historian and collector, and the scientific coordinator of the Master in Economics and Management of Art and Cultural Heritage Program of the Business School of Il Sole 24 Ore in Rome.